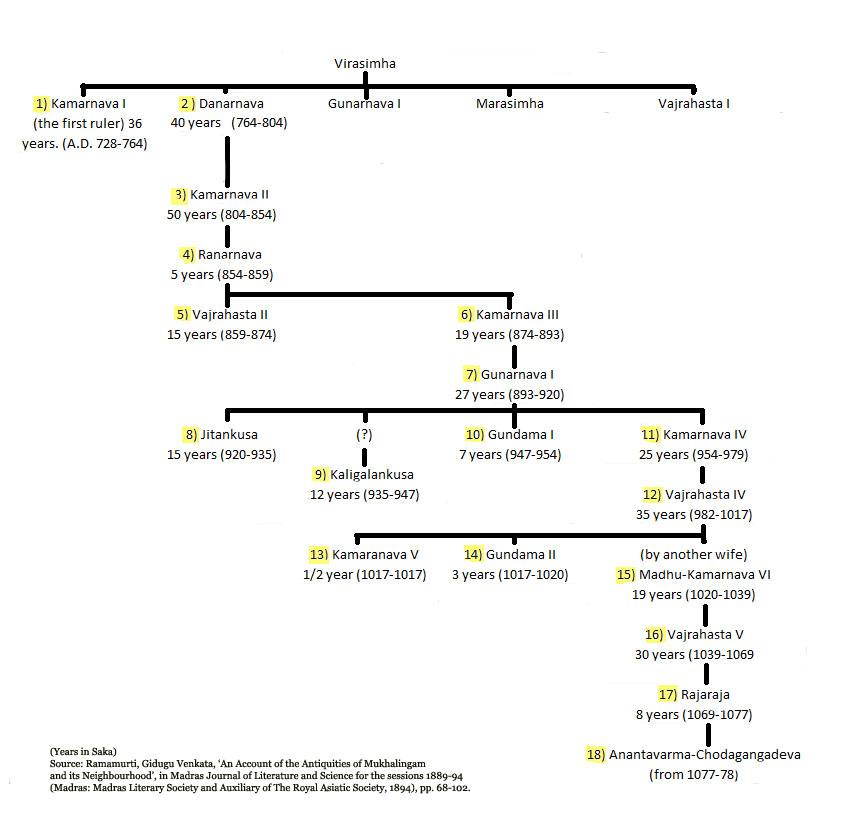

Sri Mukhalingasvara Temple – Mandapam entrance

These are two of the three ancient temples located in the village of the same name as the first temple mentioned in the title. It took many wrong turns to finally get to the right road to this village. When I visited (two years ago) Google Maps was of little help as the temple was marked way before its actual location. In fact, a recently built temple was at the place where Google Maps directed me to and on seeing it, I was disappointed. I had not travelled four and half hours from Vishakhapatnam to visit a new temple. Overcoming language barriers and tolerating the heat, I doggedly stuck to my plan and that helped me find the place. Though by the time I reached Sri Mukhalingersvara Temple it was time for the deity’s afternoon rest, so I found the doors of the sanctum shut. Nevertheless, I was elated to find myself standing in front of this majestic temple. Going past the shining gilded Dhwaja Sthambha, I climbed a couple of stairs to enter the first small enclosure of the temple through the Simhadvara[1] (entrance facing east) and then through a vestibule, which hosts sculptures that depict how Siva revealed himself to Savaras,[2] to enter the main compound in which stands the main mandapam and sanctum, and other smaller temples. I decided to spend my time exploring the beautifully sculpted subordinate temples located on the four corners and, also, two other smaller shrines. The temple was under renovation, so scaffolding obstructed my viewing a few of them from close quarters.

Being a Siva temple, a very dignified sculpture of Nandi graces the entrance of the main building. it is made of black stone and sits on a raised platform under a canopy. On the four corners of the courtyard stand smaller versions of the main temple and all are dedicated to Siva. The gopuram of each possess sculptures that depict characters and scenes from Hindu mythology. Despite being quite worn out, the sculptures are beautifully crafted and embellishments that adorn the exterior of the walls of these temples add to the magnificence. Besides these on the right hand of the main temple is a small temple, rather more of an alcove, dedicated to nine forms of Goddess Durga. This was locked too but I could see the deity made of silver through the metal bars that formed the door.

Top photo is of the temple dedicated to Goddess Parvati. The second one is a closeup of the beautifully sculpted walls and entrance of one of the subordinate temples located in the four corners of the courtyard.

The legend behind the origin of the temple as given in Kshetramahamatya.

Brahma, the creator, who is deprived of his divnity, goes to Mahendragiri, a mountain in the Kalinga country, a cursed tract, unworthy to be the abode of an Arya. He undergoes there a severe penance. Siva, who is pleased with his austerities, offers a boon. Brahma requests him to sanctify the Kalinga country by his presence on the bank of the Vamsadhara river, to which Siva assents. The Fates so contrive that certain Gandharvas are cursed by Vamadeva, for an act of indiscretion with the Savara women, to be born as Savaras, but they are to regain their former status on seeing the divine form of Siva which is in time to be revealed to them. So Gandharva-Saravas live in the forest of madhuka tress, to the west of the Mehendra Hill, on the bank of the Vamsadhara, near the city of Jayanta. The Savara chief has a wife and a Saiva concubine of Srisailam. The two women quarrel for a madhuka tree, which the chief cuts off; when lo! The divine light of Siva issues forth from the hollow of the broken trunk… Brahma, Vishnu, and all the gods come to glorify the event. Brahma brings there ten millions of lingas. Visvakarma builds beautiful temples of gold and gems.[3]

The temple doors opened dot at 2 PM and I managed a very fulfilling darshan as very few people were present. The Sanctum Sanctorum is a very tiny room in which the huge swayambhu Lingam occupies a considerable space. After the darshan I tried to get some information from the head priest but again language barrier caused me much trouble. Nevertheless, one important thing I could glean from him was that the temple was built in the fourth century of the Common Era.

Standing on the left bank of the Vamsadhara River and about 20 miles from the town of Parlakimedi. Up until the twentieth century, the Zamindar of Parlakimedi kept the temples in good repair and made adequate endowments for their upkeep. The three temples are dedicated to Siva. This tract was considered as holy as the city of Benares. G. V. Ramamurti, a highly respected Telugu scholar, visited the locality In the 1890s. A few months before his visit, the local Talukdar, at the behest of the Government, made extensive arrangements for the Shivaratri celebrations when thousands of devotees made their way to the temples,[4] confirming the importance of this place as a religious centre till at least the end of the nineteenth century.

Ramamurti gives a detailed account of his findings in the three temples and ruins lying scattered in the area and presents a convincing argument to suggest that Mukhaligam village was once the capital Kalinganagara of the Kalingas.[5] This contention got legitimacy in 1927 when the Andhra Historical Research Society celebrated ‘Kalinga Day’ in the Mukhalingam village. To mark this occasion a commemorative volume titled ‘Kalingadesacharitra’ written by the R. Subba Rao was released.[6] Subba Rao in his another article mentions that many inscriptions record land grants by public officials to the deity called ‘Kalingavani Nagare Srimanmadhukesvaraya’ which shows that Kalinganagara or capital of the Kalingas was this village.[7] The earliest name of the village was Jayantapuram, and since the idol in the Mukhalingesvara temple is referred to in the inscriptions found on the walls of the temple as Madhukeshvara, the village was called Madhukesvaram and its name was changed to Mukhalingam a few years before Ramamurti’s visit.[8] But Ganjam District accounts published previously to his visit refer to the place as Mukhalingam and not as Madhukesvara.[9] This Mukhalingam village is identified as Moccalingam mentioned in Pliny’s account of India.[10]

Ramamurti discovered some inscriptions on the walls of the Mukhalingesvara temple which were accidently exposed when plaster covering them came off over a period. Thus, other inscriptions still lie hidden behind the plaster that form the covering of the ancient original walls and therefore are not available to expand our understanding of the history of the temple and its surroundings. Those few inscriptions that have been revealed by the coming off of the plaster reveal the name of King Anantavarmadeva (Anantavarma Chodagangadeva) as being the ruler during the time when significant private donations of gold, land or money were made to the temple.[11]

One of the intriguing finding by Ramamurti from among the eleven exposed inscriptions was that one of the inscriptions was in Bengali Nagari characters. This he found on the southern gateway of the temple. Ramamurti could not read this inscription so we have no clue as to its contents. Regretfully, I was not able to see the inscriptions inside of the temple as it was dimly lit and, also, photography was prohibited. The finding of a Bengali inscription is exciting because it raises several important questions. Who were the people who visited this place from Bengal? Did Bengali traders make their way this far south? What were the goods or products they traded in? Was Mukhalingam a flourishing mart or a place of production of something important? Or was it that this temple was an important place of pilgrimage those days which drew devotees from Bengal? It is extremely vital that more inscriptions should be unearthed from behind the plaster to further our understanding of the Ganga Dynasty, or even their predecessors the Kalinga, as also the socio-religious conditions of the time. Not only does this apply for the area in which these temples are located but also for other regions from where people or traders flocked to this place. This possibility is confirmed by the inscription in Nagari characters located on the wall of the storeroom right next to the garbagriha.[12] Such findings increase the likelihood of the existence of inscriptions in other languages and scripts, and also from a far ancient time, behind the plaster. According to R. D. Banerji, the temples and ruins in the area extending to the sea near Kalingapatnam suggest that these belong to the early centuries of the common era when the Kalingas ruled over the area. Banerji contends that some remains of the Kalinga empire go back to the first and second century BCE. One of these remains is the temple at Mukhalingam.[13] According to Douglas Barrett, the oldest amongst the three temples is Sri Mukhalingesvara Temple. Barrett quotes Ramamurti extensively in his short article on the temples but disagrees with him on the question of the oldest temple.[14]

Subba Rao, an accomplished scholar whose focus of study was the Kalingas, has written extensively on the copper plate inscriptions and about their bearings on our understanding of the Kalingas and their successors the Eastern Ganga dynasty that ruled over an area encompassing modern north Andhra Pradesh and south Orissa – the area falling within the Ganjam and Srikakulam districts.[15] He provides a detailed analysis of epigraphic sources found in the area and agrees with Ramamurti’s inferences of the temples. Similarly, H. C. Ray presents a detailed account of the Ganga dynasty based on epigraphic sources found at Mukhalingam.[16]

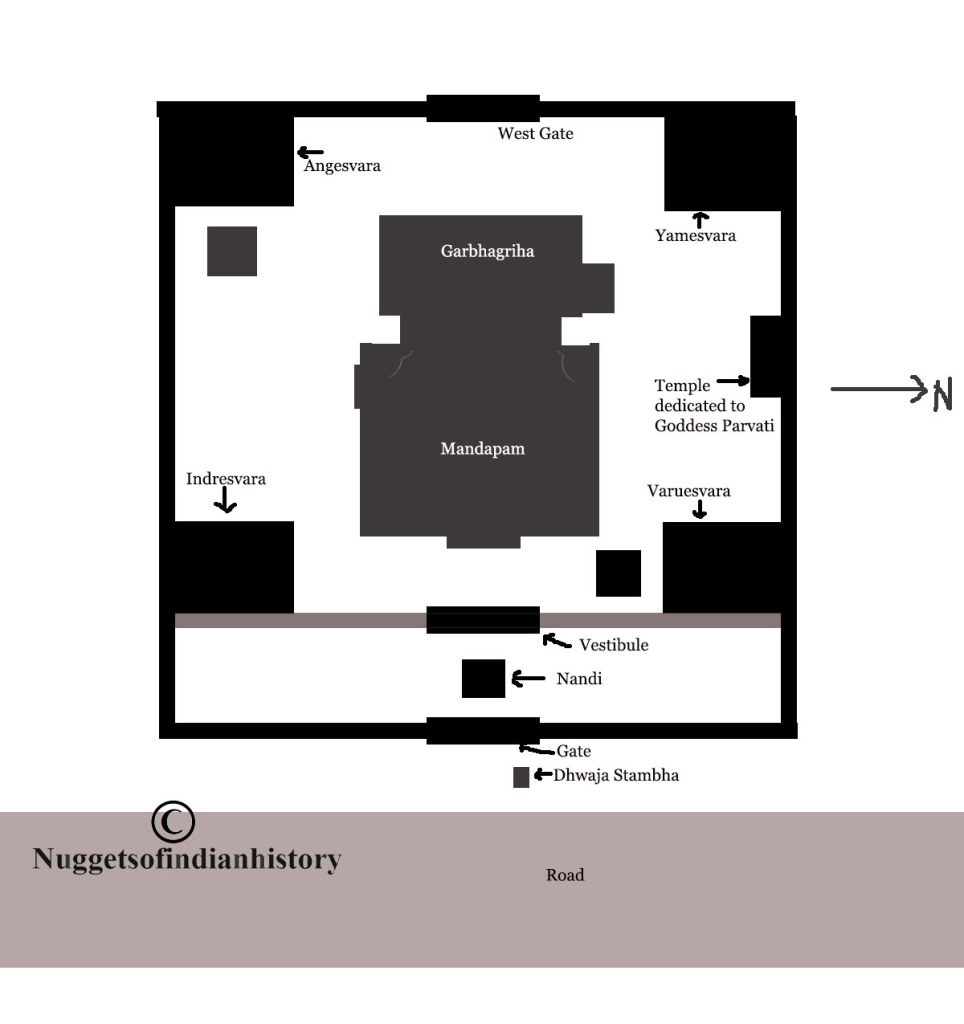

Layout of the temple complex.

As for the rest of the inscriptions studied by Ramamurti, Anantavarmadeva finds mention in several. The years mentioned in the inscriptions range from Saka 1004 to 1100 and Anantavarmadeva is mentioned in the ones dated 1004 and 1042 Saka,[17] indicating his years of reign. Ramamurti states that the antiquity of the temple could be older because some inscriptions of older characters were found which he was unable to read.

The four subordinate temples located on the four corners of the compound are dedicated to dikpalakas (guardians of the directions) – Indresvara (southeast), Angesvara (southwest), Yamesvara (Northwest), and Varunesvara (northeast). The temple is without a pradakshinapath so is a nirandhara style of temple.[18]

On the left is Yamesvara Temple and on the right is Varuneswara Temple. Both are subordinate temples to the main one.

The Someswara Temple located short of a kilometre from the first mentioned temple, opens to the west. This is a peculiarity, according to Ramamurti. The structure that still stands today is just the garbagriha, therefore a much larger complex would have existed, as deduced by Ramamurti from the existence of stone debris lying around the temple.[19]

He mentions that part of the top part of this temple was damaged by lightening some time before his visit. According to him, the construction of this temple calls for special consideration as it a rare form of architecture. The temple is built with loose sculpted stones which are placed skilfully to fit into one another like a jigsaw puzzle without the aid of cement like substance. The style of the temple is Orissa style.

Somesvara Temple: The photo on the left is of 1981 from M. Krishnamurthy, ‘Some Important Temples of Andhra Pradesh’, in Itihas, Journal of Andhra Pradesh State Archives, Volume III, no. 1 (1981), Plate VII, pp. 159-172. The one the right was taken by the author of this article in 2018.

Everything here is skillfully executed. The carvings are all of exquisite workmanship and elaborately ornamented. The figures, representing various deities of the Hindu mythology, are excellent specimens of Hindu sculpture, tastefully executed, graceful in form, and chaste in design. Each of these deities occupies a splendidly carved cell or niche standing in bold relief; in some cases it is a monolith, in others it is formed of loose stones fitted into one another. The forms of these niches are various, triangular, circular and so on. The gateway is surmounted by an excellent frieze, representing the Navagrahas, the nine Hindu planets – very beautiful figures.[20]

Nine Planets or Navagraha on the doorway

Some of the sculptors of gods and goddesses in niches on the exterior wall of Somesvara Temple

Ramamurti contends that this temple to be the oldest of the three temples located in Mukhalingam. Based on the inscriptions, the temple structure and architecture, and mythological account in the Kshetramahatmya, Ramamurti came to the conclusion that Mukhalingam village had been in existence since the eight century of the common era, and he credits the Ganga Prince Kamarnava for having founded the town. Another prince of the same dynasty and same name as Kamarnava built the temple in the ninth century. By the twelfth century, during the rule of Anantavarman, the place achieved a flourishing status. He further adds that Prince Madhukarya repaired that temples in the fourteenth century. All the named princes belonged to the Ganga dynasty, and so did the zamindar who was in possession of the temples at the time Ramamurti visited which led Ramamurti to conclude that Mukhalingam temple and the town had been in ‘uninterrupted possession’ of the Ganga Dynasty and its descendants for eleven centuries. [21]

References

The script you mentioned is Purvi Nagari (Eastern Nagari) and not Bengali Nagari. If you check the alphabets, its closely resembled to Odia script though entirely not circular.

LikeLike

You could be right, Sir. I have just cited a historian on this script. And apologies for such a delayed response. Request you to share further sources on this. As I have mentioned in my article, I was unable to view the script so I cannot comment on it. Thank you and regards

LikeLike