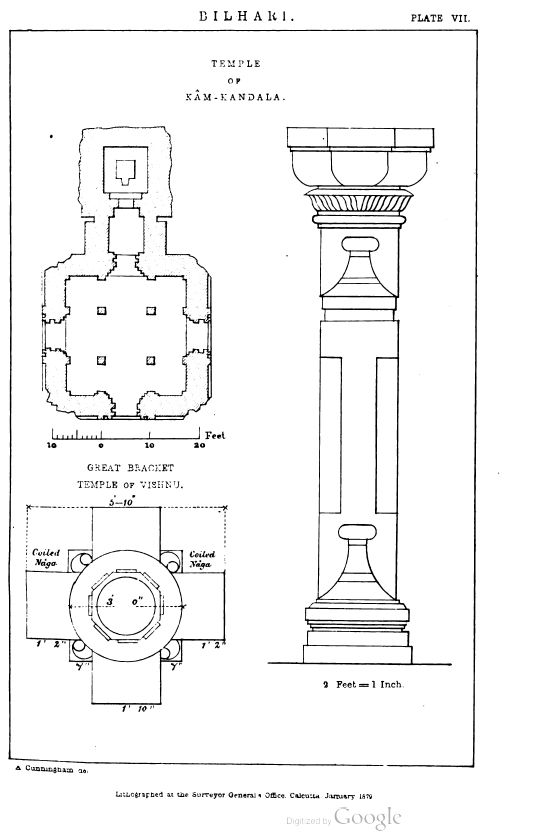

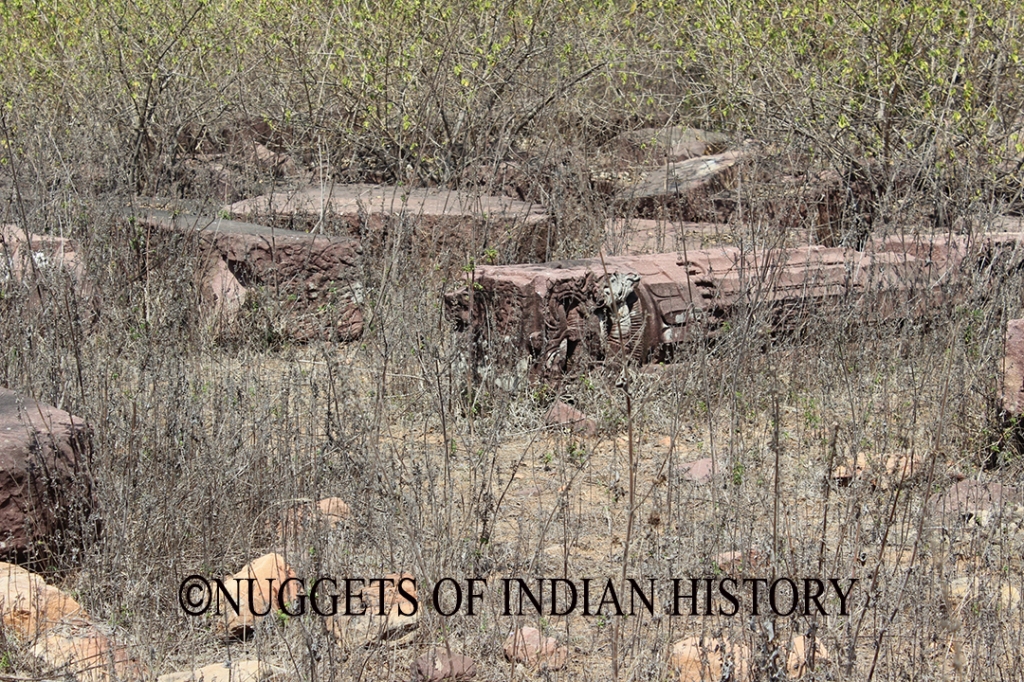

At a short distance from the town of Bilhari, lying scattered in the shrub jungle are the remnants of a massive structure that must have once been a grand temple. Going by the size of just the amalaka (top stone) of the now non-existent shikara of this temple, one can easily establish a pretty accurate scale of the temple. Thousands of stone pieces with carvings which are now largely eroded lie all around what was once the main temple structure. When I visited in early 2022, the raised platform of the temple was intact. On approaching the platform, a couple of broken steps lead to a small square platform which is connected to a larger rectangular platform leading to the mandapam pillars. The floor plan for the temple as given by Alexander Cunningham is shared below. When Cunningham visited the place in the mid-1870s, he writes the following description,

After cutting some bushes, and pushing aside some of the smaller stones, I found that Kam Kandala’s palace was only a temple of Mahadeva, with the lingam and argha still standing in situ in the ruined sanctum. The entrance of the temple faced the west, which is a very unusual arrangement, except where the buildings forms one of the subordinate shrines grouped around a large temple. But this could not have been the case with Kam Kandala’s so-called palace, as it is a large building, 54 feet in length by 32 feet in breadth, with pillars in the mahamandapa, or great hall, 10 feet 8 ½ inches in height. [1]

Source: Alexander Cunnigham, Report of a Tour in the Central Provinces in 1873-74 and 1874-75, Vol 9 (Calcutta, Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, 1879), Plate VII

But in 2022, there was no lingam nor could I see any argha. I did see a long slab of the stone placed where the lingam should have been. Some stone blocks were placed haphazardly like a jigsaw puzzle though incorrectly to create a short wall. The carvings didn’t align nor did the shape of the stones. The photos below speak loud enough about the poor condition of the site.

The locals of that area called this structure and other structures found in the area as being Kamkandala’s palace which led Cunningham to call it such. During his visit he describes visiting another structure just down the hill, less than a mile to the southwest of the ruins of the first temple, a 200 square feet courtyard “surrounding the ruins of a second temple” which, according to Cunningham, was universally called as the elephant stables (hastal) where Kamkandala is believed to have kept her elephants.

Now who was this Kamkandala? Cunningham narrates the following:

In Puphavatinagari (old named of Bilhari) reigned Raja Govind Rao in the Samvat year 919, or A.D. 862. He had a very handsome Brahman attendant name Madhavanal, who was especially skilful in singing and dancing, as well as an adept in all arts and sciences, so that all women fell in love with him. The husbands complained to the Raja and Madhavanal was banished from Phuphavati. He retired to Kamvati, the capital of Raja Kam Sen, who was fond of music and singing, and gave the Brahman a place in his sabha, or assembly. This Raja had a most beautiful woman named Kam Kandala, with whom Madhavanal fell in love, for which he was expelled from Kamvati. He then went to Ujain, and asked a boon from Raja Vikramaditya, who was famed for granting every request that was made to him. The promise was duly made, and the Brahman claimed to have Kam Kandala given up to him. Vikramaditya accordingly besieged Kamvati, and captured Kam Kandala, who was at once made over to Madhavanal. After some time, with Vikrama’s permission, the happy pair retired to Puphavati, where Madhava built a palace for Kam Kandala on the Patpara hill, which is universally identified with the ruined temple of Mahadeva…[2]

Cunningham further adds that the above narrated story is based on a folklore called Madhavanalakatha. The meanings of the names Madhavanal and Kamkandala being “sweet flame” and “love-gilder” respectively. He states the existence of this legend in the library of the Bengal Asiatic Society which was written in C. E. 1530. With the help of Babu Rajendra Lala, he gets the gist of the story.

…[The legend] recounts the amours Madhavanal and Kam Kandala, who are said to have resided at Pushpavati in the neighbourhood of the palace of King Govinda Chandra. In the legend he is called simply Govind Rao, and his date is fixed as Samvat 919 or A.D. 862, if the era of Vikramaditya is meant. But it is more likely that the local Samvat of Chedi is intended, which would fix the date in A.D 1168. It is, therefore, not at all impossible that Govinda Chandra of Kannuaj is the king alluded to. We know, however, that the country north of Bilhari was still in possession of the Chedi kings in A.D. 1158, when the Bharhut inscription was engraved on the rock of Lal Pahar… [3]

On further research, I came across several versions, however with very slight variations, of the same love-story by several authors and playwrights. An author named Ganpati wrote Madhavanal-Kamkandala in Gujarati in A.D.1528.[4] This same source mentions the existence of four versions of the same legend though details such as authors and dates are not mentioned.[5] Two manuscripts, both from early 1800s, on the same legend were listed in the catalogue of the Biblioteca Nazionale (Rome).[6] Another version titled Madhavanal-Kamakandala Prabandha, though written by the same author Ganpati mentioned above. In this version the translator gives the name of the author of this legend as Ganapati who was son of Narasa, a Kayastha residing in Amod, in the district of Bharuch, Gujarat. The legend was written in poetry form which had “2,500 doha couplets (dogdhaka), divided into Eight Parts or Angas.” The date of this manuscript is 1528 A.D. The author of the above source mentions that he later finds another manuscript of the same poem in the Fort library, Bikaner.[7] In A.D. 1584, a decade after Akbar invades Gujarat, Raja Todarmal gets a Muslim writer Alam to write the story of these two lovers in Hindi “for the pleasure of Emperor Akbar, whose exploits were comparable to those of King Vikrama and Bhoja.”[8]

Majumdar presents greater details of the story in his translation:

In the city of Puspavati, where Kamasena rules, lives a Brahmana youth by name Madhava, as ‘handsome as Love’. The women of the town run after him, and the citizens beseech the king to get rid of so fruitful a source of trouble. The king, in a judicious mood, tries to test the intensity of the fascination exercised by the boy by bringing him before his queens. Finding him, however, a danger to his own domestic peace, the king promptly banishes him.

Madhava, wandering from place to place, comes to Amaravati. His extraordinary intelligence immediately draws the attention of the local king, who gives him an honoured place in his court. A courtezan-girl, Kamakandala the favourite of the king, is at the moment exhibiting her first dance in the public. Madhava watches her performance. Admiring her skill in dancing, undisturbed even by a bee which alights on her dress, he presents to her the very betel-leaf which the king had presented to him as a mark of honour.

The king angry at the scant courtesy shown by Madhava to the royal present, orders him to leave the town. The young man with the curse of beauty upon him, while on his way to leave the city, meets Kamkandala.

She invites him to her house. The two meet; both fall in love with each other, exchange spicy riddles and their spicier solutions, and are happy. In the morning both part from each other with breaking hearts.

Madhava goes to Ujjayini, and describes his distress in verses, which he writes on the walls of the Mahakalesvara temple. Wandering in disguise about the city at night, as was his wont, to discover the miseries of his subjects, King Vikrama reads the verses, and he employs an old courtezan to find out their love-lorn author.

Madhava is found, and, is brought to Vikrama. Apprised of the hero’s love for Kamakandala, the reliever of distress forthwith calls upon Kamasena to give her up; and on his refusal to do so, marches upon his city with an army.

Vikrama, however, wants to test the strength of Kamakandala’s love. He goes to her in disguise, and tries in vain to win her for himself. As a further test, he informs her that Madhava is dead. On hearing of the death of her lover, Kamakandala becomes unconscious, and is on the point of death.

The King comes back to his camp, and informs Madhava of Kamkandala’s death. The poor lover also faints.

Vikrama, horror-struck at having killed a Brahmana, and a woman, wants to commit suicide. The spirit Vetala, his friend (so well-known as the hero in the Vetalapancavimsatika– stories) from the other world comes to his rescue, and revives the lovers.

They are married by the King with great pomp; and the lovers live happily ever afterwards indulging in pleasures and pastimes befitting their honoured place in society. [9]

An interesting fact about this poem is that unlike other works where Goddess Sarswati or God Ganesha are invoked at the beginning, here Madana (Kamdeva), the God of Love, son of Rukimini and husband of Rati is invoked.[10]

Madhavanal-Kamkandala being a popular love-story, its hero and heroine have found themselves as subjects of art works of many artists spanning centuries.

Check the following links:

https://www.rct.uk/collection/1005124/rny-khm-khndl-w-mdhw-nl-rani-kam-kandala-and-madhava-nal

https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo/kamakandala.html?sortBy=relevant

[1] Alexander Cunnigham, Report of a Tour in the Central Provinces in 1873-74 and 1874-75, Vol 9 (Calcutta, Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, 1879), 36-37.

[2] Alexander Cunnigham, Report of a Tour in the Central Provinces in 1873-74 and 1874-75, Vol 9 (Calcutta, Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, 1879), 37.

[3] Alexander Cunnigham, Report of a Tour in the Central Provinces in 1873-74 and 1874-75, Vol 9 (Calcutta, Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, 1879), 37-38.

[4] Dr. Nagendra, ed., Indian Literature [Short Critical Surveys of 12 Major Indian Languages and Literatures] (Agra, Lakshmi Narain Agarwal, 1959), introduction p. ix (Visva Bharati Library Santiniketan) https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.97863/page/n19/mode/2up?view=theater

[5] Dr. Nagendra, ed., Indian Literature [Short Critical Surveys of 12 Major Indian Languages and Literatures] (Agra, Lakshmi Narain Agarwal, 1959), introduction p. x (Visva Bharati Library Santiniketan) https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.97863/page/n19/mode/2up?view=theater

[6] Theodore Aufrecht, Florentine Sanskrit Manuscripts (Leipzig, G. Kreysing, 1892), 34-35 https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b4179662

[7] M. R. Majumdar, Madhavanala-Kamakandala Prabandha, Vol 1 (Baroda, Oriental Institute, 1942), preface. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.382560/page/n3/mode/2up?view=theater

[8] M. R. Majumdar, Madhavanala-Kamakandala Prabandha, Vol 1 (Baroda, Oriental Institute, 1942), preface. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.382560/page/n3/mode/2up?view=theater

[9] M. R. Majumdar, Madhavanala-Kamakandala Prabandha, Vol 1 (Baroda, Oriental Institute, 1942), preface vii-viii. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.382560/page/n3/mode/2up?view=theater

[10] ibid